[vc_row css_animation=”” row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern”][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”62px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css_animation=”” row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”yes” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern” z_index=””][vc_column][vc_column_text]

English Home | Blog | About | Articles | Listen | Subscribe / Order | Contribute

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css_animation=”” row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern”][vc_column][vc_empty_space][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css_animation=”” row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern”][vc_column width=”4/5″ css=”.vc_custom_1578247142590{border-radius: 4px !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Volume 9. Number 2

The Legal and Moral Aspects of Redemption

Editorial Introduction

False views about the atonement, personal salvation, and the nature of sin can’t long survive if we rightly understand the message in this issue of Present Truth. While not exactly a bedtime story we believe its careful reading can be even more soothing to a distressed soul. Resting on the fact that the legal takes precedence over the moral does away with a myriad of needless cares in life. Understanding that the legal must always precede the moral simplifies thousands of life’s decisions. And believing that the legal is the only true basis for the moral frees us to live truly moral lives on this earth.

This issue contains a powerful, condensed reprint of a three part series by the former editor followed by a penetrating look into God’s unlimited grace by the late Reformed scholar, Dr. Philip E. Hughes. Both articles plow new soil in understanding election.

– This editorial was written by the present editor and appears in Present Truth Vol. 9 #2.

The Legal and Moral Aspects of Redemption

Part 1: Three distortions

The Protestant Reformers were the great destroyers of legalism in the church. But it was by emphasizing the legal over the moral that they uprooted legalism. They taught a legal justification based on a legal doctrine of atonement.

The Protestant Reformation was born out of the conviction that justification was a legal word – a forensic transaction. The Reformers did not devalue man’s moral renewal, but they were careful not to include the moral change in justification itself. To be sure, justification opened the door to the new life in the Spirit and bore the fruit of transformation of character, but the root was not confused with the fruit.

Later Protestants like John Wesley insisted that it was vain to talk about salvation by imputed righteousness while the heart remained a stranger to the renewing power of the Holy Spirit. Yet he too believed that justification was a change in legal standing.

Today, however, in one way or another the moral aspects of redemption (new birth, regeneration, sanctification, new life in the Spirit, etc.) have actually supplanted the legal aspects of redemption (substitution, imputation, justification, etc.). This repudiation of justification (sometimes overt and conscious and sometimes covert and unconscious) takes three forms:

Form 1 elevates the moral above the legal.

Form 2 completely identifies the legal with the moral so that there is no distinction between the two.

Form 3 does away with the legal aspects of redemption altogether.

Herman Ridderbos pinpoints the evolution of the doctrine of justification with these incisive comments:

“While in Luther and Calvin all the emphasis fell on the redemptive event that took place with Christ’s death and resurrection, later under the influence of pietism, mysticism, and moralism, the emphasis shifted to the process of individual appropriation of the salvation given in Christ and to its mystical and moral effect in the life of believers.” – Herman Ridderbos, Paul, An Outline of His Theology, p.14.

This drift away from the objective stance of the Reformation has not all been planned and deliberate. Most of it has probably been unconscious simply because human nature naturally gravitates to focus more on itself and what can be done in itself than upon what God has done outside of itself in Jesus Christ.

The more liberal wing of the Christian movement has moved away from the concept of forensic justification as preached by the Reformers, and it generally knows it. The more conservative wing of the church has also moved away from the Reformation doctrine, but in the main does not know it.

The fact is that the popular evangelicalism of today does not really have a doctrine of justification. The moral change of the new birth experience has either supplanted justification or is understood to be the essence of it. The modern evangelical thrust is generally based on the appeal to “Let Christ come into your heart.” The great legal aspects of redemption are lost in the preoccupation with religious experience.

The Issues at Stake

Because we contend for the restoration of forensic justification to the primary place in redemption, some will doubtless interpret this as an attempt to devalue the renewal of man. However, it is not those who contend for the primacy of the legal aspects of redemption who really devalue sanctification, but the opposite is true. Those who ignore the primacy of forensic justification remove the true foundation of moral renewal.

The most terrible consequence of ignoring the legal aspects of redemption is that one really ends up making the cross of Christ of none effect. If we could be saved simply by inviting Christ to come into our hearts to effect a moral transformation, then we must say with Luther that Christ labored foolishly and suffered in vain if God could save us simply by an inward transformation. Or are we going to say that what happened at Calvary was merely a moral influence to inspire us to deal with sin in our personal experience?

The Bible is clear that God’s righteousness did something in the Christ event. Sin was dealt with, Satan was defeated, death was destroyed, and redemption was accomplished. And this mighty action of God, which transcends every other action for all eternity, was not a work done in us (moral), but was a work done outside of us in the Person of Christ (legal). As the old theologians used to say, the atonement was the satisfaction which Christ gave to the divine law on our behalf. It was the fulfilling of the terms of the legal covenant by our Representative in order that God could forgive sinners without sacrificing the honor of divine justice. Our justification is great because it is founded on such a great work – a work far greater and infinitely more glorious than our moral renewal: as great as that is.

The Reformers proclaimed that Christ both fulfilled and satisfied the claims of God’s law on our behalf. If sinners can be justified solely by faith in the satisfaction that Christ gave to the law, and if the life and blood of the Lord of glory are the price of their justification, then it is forever certain that they cannot be justified by anything done by them, nor by anything done to them, nor by anything done in them. Legalism is damnable, not because it is legal (lawful, righteous), but because it is illegal (unlawful, unrighteous). Legalism offers to the law less than it requires. When the sinner sees Calvary and understands that this is exactly what the law requires for justification, he will not presume to offer anything less to the law.

The legal view of the atonement and justification kills legalism and is the only basis of moral renewal. On the other hand, the moral influence theory of the atonement and the moral renewal view of justification lead inevitably to legalism because they ground salvation on some phase of the human experience – whether that experience is said to be faith, new birth, baptism, new life in the Spirit, or the new obedience of the believer. Only the Lutheran truth concerning justification brings joy to the religious life.

The two aspects of salvation – the legal and the moral – must be maintained in soteriology as strenuously as we maintain the two natures of Christ in Christology. Both distinction and harmony must be upheld. True and original Protestantism affirmed both the legal and the moral aspects of salvation. It refused to subordinate the legal to the moral, but affirmed the primacy of the legal in three major areas:

1. In the matter of sin the primary problem was seen as guilt (legal) rather than pollution (moral).

2. In the nature of the atonement the primary work was satisfaction to the law (legal) and not just a demonstration to change man’s idea about God (moral).

3. In the application of redemption, justification (legal) must precede and be the foundation of sanctification (moral).

Much is at stake here. If the legal aspects of redemption are lost, the doctrine of justification is lost. And (as Luther often warned) if justification is lost, all true Christian doctrine is lost, and nothing remains but darkness and ignorance of God. We are faced here with a situation which could spell the absolute demise of Protestantism and the triumph of the opposite stream of religious thought. Or to put this another way, we face the rejection of revealed religion in favor of the religion based on the religious insights of human nature.

Part 2: The legal over the moral

In Part 1 we saw that there are two aspects of salvation – the legal and the moral. Sin is guilt (legal) as well as pollution (moral). The atonement was a satisfaction made to the divine law (legal) as well as a demonstration of God’s love to change our hearts (moral). Salvation consists in a change in our standing before the law, which is called justification (legal), as well as a change in our state, which is called sanctification (moral).

In the centuries which followed the apostolic age the church increasingly confused these two aspects of redemption. This meant that man’s right standing or acceptance with God was made to rest on his personal moral renewal. While it was maintained that this moral renewal was accomplished by grace, salvation still rested on the internal righteousness of religious man.

It is probably true that the church was unable to grasp the truth of Pauline theology until she had adequately tried the alternatives and found them bankrupt.

At any rate, the Reformers made a clear distinction between the legal and moral aspects of redemption (i.e., between justification and sanctification). They went further and maintained the primacy of the legal over the moral. This was a revolution which broke through the medieval system and swept the consciousness of Western man with such tempestuous fury that it changed the history of Christendom – religiously, economically, politically and socially.

The Primacy of the Legal

1. In the Matter of Sin. Sin must be viewed as guilt (Rom. 3:19) as well as pollution (Job 14:4; Jer. 17:9). In the theology of Romanism sin is thought of primarily in terms of pollution. Consequently, salvation is thought of primarily in terms of moral renewal. That which makes a sinner acceptable to God is said to be an inner transformation (gratia infusa) which removes the offense of inner pollution. Original Protestantism, however, being a revival of Pauline thought, saw sin primarily as guilt – man’s indebtedness to the law.

Here we see a strange paradox. The opponents of the Reformation saw sin primarily as a moral defect in man, but they had a shallow view of the utter ruin of man and how that moral defect permeates every part of his existence. The proponents of the Reformation saw sin primarily as man’s guilt before the law, yet it was they who had such a profound view of man’s moral condition that they held the doctrine of “total depravity”– that there is no part of man’s existence that is not tainted with sin.

2. In the Matter of the Atonement. There are two major aspects of the atonement. (1) There is the aspect of Christ’s bearing our judicial punishment or penal satisfaction. This is often (and rightly) referred to as the substitutionary death of Jesus Christ. (2) Also, there is the aspect of the revelation of God’s love to the darkened mind of sinful man.

When the second aspect alone is stressed (or even overshadows the first), we have what is known in theology as “the moral influence theory of the atonement.” It goes along with the idea that sin is not a legal problem (guilt) but solely a moral problem (pollution). With a good deal of plausibility it argues that it was not God but man who changed in the Fall, and therefore salvation only consists in changing man. Man’s heart needs reconciling to God, and in order to effect this change God must give man such a demonstration of His love that it will work the needed change of attitude in the sinner. The cross is this revelation. In this theory salvation was not wrought out at the cross, but it is a subjective process wrought out in the heart of the sinner. When he repents and believes in God’s love (which the cross enables him to do), he is declared right because he is now morally changed and is therefore in a right relationship with God.

We do not deny that there is a great moral influence factor in the atonement. After all, did not Paul say that the love of Christ, demonstrated in His dying “for all,” constrained him to live for Christ (2 Cor. 5:14, 15). The error of the moral influence theory of atonement lies more in what it denies. To be specific:

a. It denies the reality of the divine law, its sentence against sinners, and the wrath of God incurred because of sin.

b. It fails to appreciate that the reconciliation in Christ’s act of atonement was something which took place for us and in our interest while we were still God’s enemies (Rom. 5:10; Col. 1:20-22). This was therefore something which took place objective to us and was not a subjective process.

We must remember that the apostles wrote out of the background of the Old Testament and the whole history and education of Israel. The basis of this background was law and the demand for righteousness to match its claims. The evangelical message of the New Testament is always presented in its relation to the legal demand of the Old Testament. In the book of Romans, for instance, Paul is careful to reiterate the inexorable legal demand (Rom. 2:13) before he goes on to show how this demand is met in Christ’s substitutionary work. This is not negation of the law but its true honoring (Rom. 3:31). Paul only negates law as a method of salvation, not as a valid demand of a righteous God.

The Reformers thought of the atonement primarily in terms of satisfaction rather than moral influence. In this they followed on from Anselm rather than from Abelard. In the eleventh century Anselm had done some great work on the doctrine of the atonement. He argued for the necessity of the atonement on the grounds of the holiness of God’s nature, and in this he made a great contribution. But he still left the doctrine largely in the realm of the abstract. The Reformers were the first men since the apostles to concretely relate the atonement to the law of God. Says Dr. George Smeaton:

“A further explanation of truth was reserved for the Reformation, by penetrating more deeply into the nature of the divine law than was ever discovered by the great scholastic [Anselm]. What his theory wanted, indeed, was a full recognition of the claims of the divine law, and of the atonement as a satisfaction of these claims in all their breadth and extent….

“Previous theories wanted a full recognition of the claims of the divine law, and of the atonement as a satisfaction of these claims in all their extent; and this became the element in which the theology of the Reformation moved, and by which all other truth was coloured…. Their main position, to which they were conducted by deeper views of the extent of the law, and of its unbending claims, was that Christ’s satisfaction was perfectly identical with that which men should themselves have rendered; and in the atonement they read off the unalterable claims of the divine law.” – George Smeaton, The Atonement According to Christ and His Apostles (Sovereign Grace Publishers, Grand Rapids, Michigan).

We will not here take the time and space to cite many references from Luther and Calvin which amply support what Smeaton says. Anyone who takes the trouble to read these Reformers will know that they believed Christ’s death was made necessary by God’s law. They taught that the atonement was the satisfaction rendered to the divine law on our behalf. That which God’s law required He provided for us in the doing and dying of Jesus Christ. His atonement was all that God’s law requires of us, so that any man who believes in this is credited with all that Christ has done on his behalf and therefore stands as righteous in the eyes of the law. Faith in the atonement is not seen as a means of setting aside the demands of the law but as a method of meeting them.

When we see Christ’s death in its relation to the law (legal), it shows us the perfect blending of justice and mercy, the sacredness of God’s law in that it could not be set aside, and the unrelieved heinousness of sin, which is the transgression of God’s law (1 John 3:4). Only in the light of this legal view of the atonement will the moral influence have proper content. Any reformation of life and conduct which is not based on God’s law is a religious phony. Of course, God’s love revealed in the cross demands something! Jesus said, “If ye love Me, keep My commandments” (John 14:15). While the law points us to Christ, Christ points us back to the law. But the so-called “moral influence” of the cross cut loose from what the cross was primarily about (satisfaction to God’s law) becomes the phantom of human sentiment.

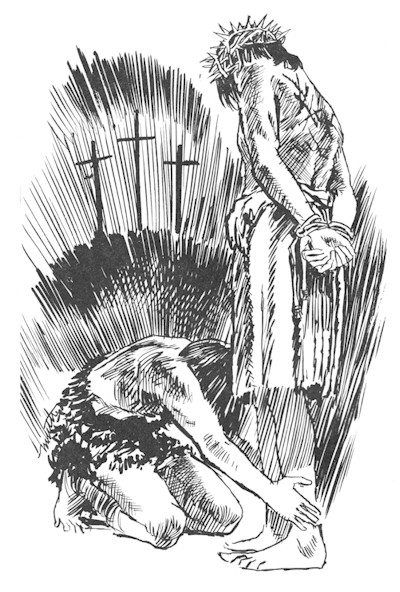

If anyone has the slightest doubt about the supremacy of the legal over the moral, let him consider how God dealt with Jesus Christ on the cross. As touching His moral condition, Christ was the righteousness of God. As touching His legal position, He was “numbered with the transgressors.” Justice dealt with Him not according to what He was in Himself, but according to His standing in the eyes of the law. We might even say that when the sins of the world were imputed (legally reckoned) to Jesus Christ, He was treated according to His legal position and not according to His moral condition. The legal took precedence over the moral.

There is an eternity of comfort here for the believer. He realizes that the righteousness of Christ is imputed (legally reckoned) as his, and in the eyes of the law he stands as righteous as Christ Himself. God does not deal with him on the basis of his sinful state but on the basis of his righteous standing.

What comfort and security, therefore, is found in the truth that the legal takes precedence over the moral! God does not deal with us on the basis of what we are in ourselves, but He treats us according to what we are in Jesus Christ.

3. In the Matter of Soteriology. If sin is primarily guilt before the law (legal) and if the atonement is a satisfaction to the law (legal), it follows that the legal aspect of personal salvation must take precedence over the moral aspect. The biblical word justification is a juridical word relating to trial, judgment and law. It is the verdict of the Judge that the one tried stands righteous in the eyes of the law. The verb justify means to declare righteous and not to make righteous. If justify is taken as a making righteous in the subjective sense, then it becomes confounded with sanctification.

Any doubts about the legal meaning of justification should be put to rest when the how of justification is considered. In Romans 4 the apostle uses the word logizomai (impute, reckon, count) eleven times. Its meaning is transparently clear. The believer is credited with Christ’s righteousness because Christ obeyed, even unto death, in the believer’s place (Substitute) and in the believer’s name (Representative).

The Reformers were not only careful to maintain the legal nature of justification and to distinguish it from sanctification (the moral change), but they contended for the primacy and supremacy of justification over sanctification. Fellowship with God cannot be based on the experience of sanctification but on the imputation of Christ’s meeting the claims of the law for us. We can never in this life reach a point in sanctification where fellowship with God does not rest on forgiveness of sins.

It was Rome’s great contention that the Protestant doctrine of forensic righteousness was subversive to sanctification. By making acceptance with God rest on inner transformation, Rome argued that she was putting the true value on sanctification.

A true view of theology and history, however, will show us that here was Rome’s most fundamental mistake. Calvin’s Geneva or Anglo-Saxon Puritanism were not conspicuous for their lack of moral fervor. Could the same thing be said of communities in Spain and southern Europe where the light of the Reformation never penetrated? The fact is that the legal aspect of salvation is the true root of moral renovation. Justification is the mainspring of sanctification. Unless the moral aspect rests on the legal and derives its life and direction from the legal, it must wither and die. In fact, it is no longer moral but immoral.

Our fellowship with God is not founded upon our experience of sanctification but upon the oath of the covenant. The idea of covenant runs through the entire Scripture. Covenant is a legal word. It is a contract. Justification constitutes us “married” (legally) to Jesus Christ (Rom. 7:4). God will be no party to spiritual fornication. We must become legally (lawfully, rightfully) His by divine pronouncement before He can live in union with us. Or to change the figure (but not the truth), we must be legally adopted as sons before God can send the Spirit of His Son into our hearts (Gal. 4:5, 6).

Prior to justification the Spirit works upon the heart of the sinner in a drawing, wooing process leading to faith and repentance. After justification the Spirit indwells the believer. The difference is as clear as the relationship of a man to a woman before and after marriage.

If fellowship with God rests on sanctification, what can the believer do in the day of darkness and trial when he stumbles or is surprised into failures and mistakes? What right can he now claim to fellowship with God when he is vividly confronted with human sinfulness before the face of divine glory? How easily would faith falter, and he would stand disarmed in the midst of his enemies, if he had no oath and covenant to flee to for refuge in the day of storm! Happy is the man who in the hour of test and trial has something better than his own fickle experience upon which to rest.

Though Satan should buffet, though trials should come,

Let this blest assurance control,

That Christ hath regarded my helpless estate,

And hath shed His own blood for my soul.

A woman who ignores a legal relationship and tries to establish a relationship with a man by experience alone is prostituting a fundamental law of life. In the Revelation of St. John, Babylon (which represents all false religion) is called a harlot (Rev. 17:5). Babylon is every system that tries to establish a relationship with God on the basis of one’s moral change. Sanctification is a moral change. Justification is its legal basis, and without justification no true sanctification can exist.

The Results of Neglecting the Legal Aspects of Salvation

Luther often said that if the article of justification is lost, all true Christian doctrine is lost at the same time. We will briefly draw attention to the consequences of neglecting the legal aspects of salvation.

1. First and foremost, the cross of Christ is emptied of real meaning. If Christ did not make satisfaction to the claims of the law on Calvary, then the cross becomes a senseless tragedy or some incomprehensible exhibitionism.

Also, as we pointed out in Part 1 of this series, if the sinner could be saved by moral renewal (Christ in the heart, Spirit baptism, etc.), then it would have been really needless for Christ to suffer and die. If there were no legal claims to meet for human salvation, the cross would be unnecessary and irrelevant. Perhaps this is why we hear so little exposition on the Christ event today but instead are drowned in the “gospel” of the changed life of the believer.

In the non-Christian religions any historical features (if they have any at all) can be eliminated without making any essential difference to the content of these religions. It almost seems that the same thing could be done with so much which passes as the Christian religion today.

2. When the legal aspects of redemption are neglected in favor of the moral renewal emphasis, man becomes the center instead of God. Instead of the New Testament’s focal point being God’s work in Christ, it becomes God’s work in the human heart. Man and his experience inevitably take the spotlight. Man, and not God, becomes the center of religion.

3. When the legal aspects of redemption are removed, the believer has no objective foundation for his salvation. The great acts of God which were done outside of the believer in Jesus Christ are no longer the object and anchor of faith. Then there is no salvation by substitution, representation and imputation. Salvation is reduced to a subjective process in man himself.

4. Sanctification which is not based on justification is not legal; and because it is not legal, it is immoral. It does not really build up the believing community but destroys it. Unless morality is based on divine law and the honoring of that law which took place at Calvary, it becomes immorality. This is why the Revelator declares that the religion of great Babylon corrupts the earth (Rev. 11:18; 17:5).

5. The drift away from, and in many cases the outright repudiation of, the legal aspects of redemption betrays the cause of true Protestantism. It spells the triumph of the enemies of the Reformation.

It is commonly thought that the Reformation, being a revolt against legalism, had no such vital interests in the legal aspects of redemption. Such is the superficial view that many have today of the issues at stake in Reformation theology. In fact, many think that they imitate the Reformers and demonstrate their antipathy to legalism by despising the legal aspects of our redemption. They fail to see that legal is lawful, rightful and righteousness, whereas legalism is a perversion of the legal. Legalism is not legal but illegal.

We need close application of thought to reason correctly from cause to effect in this matter. The moral influence theory of atonement leads inevitably to legalism. The idea of acceptance with God on the grounds of moral renewal is legalism. The concept that sin is primarily pollution (moral) and that salvation is effected merely by the process of purging away this pollution is legalism. This whole system proposes that it is the human agent who meets and satisfies the claims of justice by some personal experience (attainment) of his own.

Therefore the elevation of the moral aspects of salvation above the legal results in legalism and destroys all true morality. On the other hand, when the legal aspects of redemption are given their primacy, legalism is cast down and there is provided a strong and true basis of moral action.

The Reasons for Neglecting the Legal Aspects of Salvation

Everybody knows that the Reformation was the great enemy of legalism. But somehow a subtle evolution has taken place whereby the antipathy toward legalism has been transferred to the law itself. Gordon H. Clark points out that legalism has now acquired a new meaning. Whereas it used to designate a theory of justification by works, now it is used to designate (and denigrate) any obligation to obey objective laws – as if amorphous love replaces definite commands (Christianity Today, 3/16/73).

The fact is that the righteous God has such a passionate regard for good works and such a high standard of acceptable obedience that fallen sinners are utterly unable to meet this just demand. A man who tries to be justified by the works of the law is not condemned because he keeps the law but because he fails to keep it (see Gal. 3:10).

Reflecting on this, Calvin says, “We therefore willingly confess that perfect obedience to the law is perfect righteousness.” – Institutes, Bk. 3, chap. 17, sec. 7). “The Lord promises nothing except to perfect keepers of the law.” – Ibid., sec. 1. And Luther could even say, “The law must be fulfilled so that not a jot or tittle shall be lost, otherwise man will be condemned without hope.” – Luther’s Works (American ed.; Muhlenberg Press; Concordia, 1955- ), Vol.31, p.348.

The gospel teaches us that we are saved solely by the work of Christ. But in what did His work consist? He did for us what we were obligated to do. Says Calvin, “For if righteousness consists in the observance of the law, who will deny that Christ merited favor for us when, by taking that burden upon Himself, he reconciled us to God as if we had kept the law.” – Institutes, Bk. 2, chap. 17, sec 5. Faith is said to justify not because we are rendered righteous before God on account of faith and not because faith itself pleases God more than obedience to His law, but simply because faith lays hold of Christ’s perfect obedience, with which the law is well pleased. Unless we clearly see that justification honors and establishes the law (Rom. 3:31), we are not seeing the biblical doctrine of justification by faith.

The message of justification can only make sense in a context where the law of God is taken in the radical seriousness that the Bible demands. A man has to be pressed with his obligation to meet the claims of the law, and he must realize that there is no hope of life eternal unless the law of perfect justice is satisfied. As Luther says, he must learn “through the commandments to recognize his helplessness” and to become “distressed about how he might fulfill the law.” – Luther’s Works, Vol.31, p.348. The following comments by Dr. J. I. Packer hit the nail on the head:

“Protestants of today (whose habit it is to take pride in being modern) are accordingly disinclined to take seriously the uniform biblical insistence that God’s dealing with man is regulated by law…. Thus modern Protestantism really denies the validity of all the forensic terms in which the Bible explains to us our relationship with God.

“The modern Protestant, therefore, is willing to see man as a wandering child, a lost prodigal needing to find a way home to his heavenly Father, but, generally speaking, he is not willing to see him as a guilty criminal arraigned before the Judge of all the earth. The Bible doctrine of justification, however, is the answer to the question of the convicted lawbreaker: how can I get right with God’s law? How can I be just with God? Those who refuse to see their situation in these terms will not, therefore, take much interest in the doctrine. Nobody can raise much interest in the answer to a question which, so far as he is concerned, never arises. Thus modern Protestantism, by its refusal to think of man’s relationship with God in the basic biblical terms, has knocked away the foundation of the gospel of justification, making it seem simply irrelevant to man’s basic need.” – “Introductory Essay” to James Buchanan’s The Doctrine of Justification.

Evangelicals often have their own brand of antinomianism, cloaked in such pious-sounding phrases as “Christ will live the victorious life for you,” “Love takes the place of any external commandment,” “When you are guided by the Holy Spirit, you do not need the law.” They are wiser than Paul, who filled all his Epistles with moral and ethical imperatives.

It is perfectly biblical to preach that the law is abolished for the believer as a means of salvation, but it is sheer antinomian heresy to say that it is done away with as a rule of life. All creature existence is subject to law, and the man who says “I am subject to no law” has immediately introduced his own law – just like the fellow who gets up and says “There are no absolutes” has introduced his own absolute.

The opponents of the Reformation in the sixteenth century maintained that Luther and Calvin’s doctrine of forensic righteousness would result in moral permissiveness and a great breakdown of the social order. Many good Roman Catholics today, looking at the condition of modern Protestantism, sincerely feel that their apprehension about the Protestant doctrine is justified. For the most part, modern Protestantism is soft and flabby through lack of moral discipline. There often appears to be more respect for the divine law and reverence for God among Catholics than among Protestants; and if there is to be another and final Reformation, the most favorable soil for it might well be found outside the mainstream of modern Protestantism.

One thing is certain. Justification, which concerns the legal aspect of human redemption, will never be understood or make any sense except to those who respect God’s law and take its demands seriously. To them the doctrine of justification will be no root out of the dry ground but the sweetest message under heaven.

Part 3: In the Matter of Election

In Parts 1 and 2 of this series we showed that:

1. Sin is guilt (legal) as well as pollution (moral).

2. The atonement is a penal satisfaction to the law (legal) as well as a revelation of God’s love to the sinner (moral).

3. Salvation consists in justification with its verdict that a man stands right in the eyes of the law (legal) as well as in sanctification with its transformation of man’s character (moral).

We also saw that in correctly relating these two aspects of redemption the legal must not only be given the primacy, but it must take precedence over the moral. This was the genius and brilliant light of the Reformation. The moral renewal of man was not denied or even devalued by the Reformers, but they knew that man’s salvation must rest on the acts of God in Jesus Christ. The legal view of sin, the legal view of the atonement, and the legal view of justification did not give life to legalism. Rather, they gave legalism its “deadly wound.”

These legal aspects of redemption, comprehended by the Pauline and Reformation doctrine of justification by faith, became a great central truth which explained other truths. Luther said:

“If the article of justification is lost, all Christian doctrine is lost at the same time… It alone makes a person a theologian… For with it comes the Holy Spirit, who enlightens the heart by it and keeps it in the true certain understanding so that it is able precisely and plainly to distinguish and judge all other articles of faith, and forcefully to sustain them.” – What Luther Says, ed. E. Plass (Concordia), Vol.2, pp.702-714, 715-718.

We now want to take the Reformation insights into the legal and moral aspects of redemption and apply them to the doctrine of election. Or to put this another way, we will look at certain aspects of Reformed theology in the light of justification by faith.

All that we may know about God and election has been revealed in His Son. Christ is the truth to which the Spirit continually points. The Christ event is the truth about the future, for in His death and resurrection the events of the last judgment have already been disclosed. He is also the truth about the past. Jesus Christ is the full disclosure of what God planned from eternity. In this matter of election it is important that we determine to know nothing save Jesus Christ and Him crucified (1 Cor. 2:2).

Reformed theology

Of all sections of the Protestant movement, none see themselves as greater defenders of the Reformation heritage than those who take the name “Reformed.” The legal aspects of sin and salvation are forthrightly expressed by all good Reformed theologians. The inflexible demands of God’s law, satisfaction of its claims by Christ on the cross, the forensic meaning of justification, and the “third use of the law” all find their place in Reformed theology. There are some solid substance and sound divinity here which are sadly lacking in most other forms of “wishy-washy” evangelicalism. Folk too used to a diet of evangelical cotton candy would be well advised to read some divinity and theological substance found in such Reformed “heavyweights” as Berkhof, Warfield, Hodge, Buchanan, Denny, Smeaton, etc.

Yet in a very important area, has there been a failure on the part of Reformed theology to carry through with the principle of rightly relating the legal and moral aspects of redemption? Has the heat of controversy over the doctrine of predestination put a rift between today’s Calvinists and John Calvin himself?

Augustine’s Premise

Reformed theology has followed Augustine in its doctrine of “total depravity.” Augustine’s thinking about predestination and grace was influenced by his understanding of the condition of fallen man. Against Pelagius he had argued convincingly that fallen man is totally enslaved. In himself he has no desire to repent, no ability to believe, no inclination to come to God, and therefore no free will. The Reformers revived Augustine’s insight into “total depravity.” Total depravity does not mean that man is as bad as he can be but that the whole man, even the best in man, is tainted with human sinfulness.

Augustine reasoned out his doctrine of predestination anthropologically – that is to say, it was determined by his view of man’s moral condition. If sinners are totally lost and without free will, the positive or negative response of men to the gospel, he reasoned, has to be due to a predestination decree to elect some and pass others by. So the doctrines peculiar to the Augustinian system are logically deduced from the sinner’s moral condition.

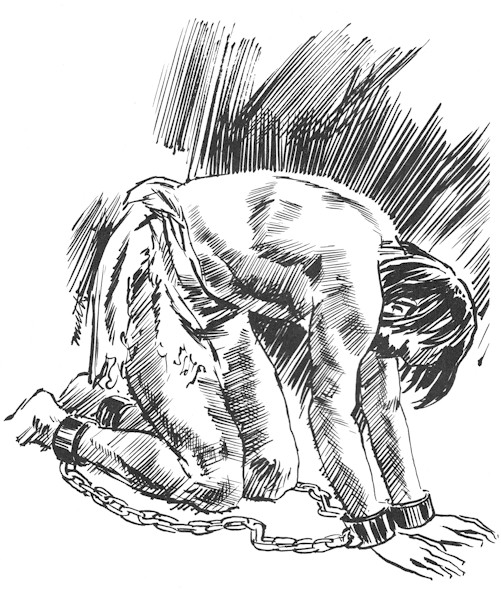

What we are again affirming is that the legal position of a man takes precedence over his moral condition. Man is not a slave due to his moral disease. He is guilty before the law. He is a slave legally. The power that holds him in prison is not that of a moral disease. It is the power of an omnipotent law (1 Cor. 15:56).

When we assert that the legal takes precedence over the moral, we do not only mean this in the matter of enslavement. We mean it also in the matter of liberation. Freedom only comes legally. When Jesus Christ was numbered with the transgressors, He was treated as a sinner, treated as if He were not in fact righteous, treated as if His moral righteousness did not exist. In other words the spiritual transformation of a man is not what gives him freedom of the will.

These are the implications of the legal and moral aspects of redemption. But Augustine did not clearly distinguish between the legal and the moral. In Augustine’s thought the sinner was in bondage due to his moral condition.

Calvin, of course clearly distinguished between the legal and moral aspects of redemption. But in the system known as Calvinism this insight was not carried through and did not determine the view of the related doctrines of grace. This has thrown the Calvinists into some utterly impossible and indefensible difficulties:

Calvinistic Difficulties

Calvinism has put the moral before the legal. Contrary to John Calvin himself it claims that the sinner must be regenerated by the Holy Spirit (the moral) before he can believe and be justified (the legal). A typical Reformed publication The Grace of God (The Banner of Truth Trust) says, “He must be born again (which is a sovereign act of God) before he can repent and believe.”

How does the Calvinist arrive at this position? By applying logic rather than revelation to man’s moral condition. He reasons that since man has no free will due to his moral condition, his inward condition must be changed before he can be free to choose to accept the gospel and be justified. In this the Calvinist has put the moral before the legal. The Calvinist has betrayed John Calvin and the heart of the great Reformation right at this point.(See John Calvin, Institutes, Bk. 3 chap. 11, secs. 6, 11; Bk. 4, chap. 2, sec. 2; Consensus Tigurinus cited by Francois Wendel, Calvin: The Origins and Development of His Religious Thought, p. 256).

In Part 2 of this series we showed that not only must the legal aspects of salvation take precedence over the moral, but the moral must be based on the legal. “Sanctification” which is not based on justification is no true sanctification at all. It is not moral but immoral for the simple reason that it is not legal (lawful). Referring again to the illustration of marriage, legal union must precede conjugal union. Otherwise it is immoral. God will never be a party to spiritual fornication. Or to change the figure, the sinner has to be adopted as a son (legal) before he is made a son vitally (Gal. 4:5, 6). The primacy of justification is at stake here, and the Calvinists have compromised it. The great moral change called regeneration or the new birth is distorted into an immoral change when it is placed before justification.

In order to consistently maintain this “illegal” ordo salutis, great scholars like Hodge have had to contend that regeneration or the new birth is only a subconscious change in man – something which takes place before the sinner knows anything about it, something done without the sinner’s consent. This would be like the groom forcing the bride into conjugal union prior to marriage, only without her knowledge or consent. Even if the bride is unconscious or drugged, such an act is illegal for the covenant has not yet been signed.

The result of this theory of a subconscious regeneration is a very weak view of regeneration The new birth is not some secret, clandestine, quasi relationship between Christ and the believer, but accompanying the verdict of justification, it is a great change in the moral state of which the believer is very conscious (Rom. 8:16; Gal. 4:5, 6). The historian Philip Schaff is right when he says that John Wesley’s emphasis on a visible, conscious regeneration accompanying justification was his great contribution. And on this point Wesley was more in harmony with John Calvin than those who generally took the name “Calvinists.” And besides, on the doctrine of justification Wesley affirmed that he did not differ from Calvin “one hair’s breadth.”

The Christological Basis of Human Freedom

We have already pointed out that the Augustinian system is anthropologically based – it starts from man’s moral condition (total depravity) and reasons out its system from that starting point. It is preoccupied with the moral aspect and attributes man’s bondage to that while it fails to appreciate the more primary feature – the legal aspect of human bondage and freedom.

But that is not all that needs to be said about human slavery. God appointed His Son to be the second or last Adam, the new Representative to legally act for lost man. Jesus Christ assumed human nature and became humanity’s new head. The government was placed upon His shoulders (Isa. 9:6). As Mankind’s Substitute and Surety He redeemed the dominion that had been lost by Adam. Having fulfilled and satisfied the law by life and death the redemption price for the race was paid (Rom. 7:4) He comes in the proclamation of the gospel with the offer of a freedom already purchased.

This does not mean, as some have contended, that because of the death and resurrection of Christ all men, ipso facto, are free to accept salvation any time they choose. The freedom is in Jesus Christ alone. Christ’s atonement was the fulfillment of the covenant between the Father and the Son. It was a legal transaction which gave Christ the legal rights and titles to man’s lost inheritance. Christ did not only purchase some men by His blood, but He bought the whole race of men.

At this point the Calvinist may ask, “How can the sinner, who is dead in sins and totally depraved, be free to accept Christ?” We simply answer that the legal aspect of redemption takes precedence over the moral condition of man. Calvary proves it! If a sinner can be legally freed, then he is free irrespective of his moral condition. The legal so transcends the moral that even the dead can hear the voice of the Son of God and live (Cf. John 5:25). Thus the objection about the total depravity of man’s nature is, at this point, a denial of the power of the gospel.

If the sinner believes, we must say that his salvation and his ability to accept Christ are wholly of grace. That ability was given him of God in the coming of the gospel. We cannot, however, explain why any man rejects the gospel. To give a reason for unbelief would be to excuse it. There is no excuse. “Why will ye die, O house of Israel?” (Ezek. 18:31). God Himself has no answer to that question. Because unbelief is so inexcusable, it is so damnable.

Does man’s unbelief mean that God stands helplessly on the sidelines? Does puny man checkmate the Almighty? No, for the Scripture teaches that even if no one believed what God has done, God’s plan and purpose has already been carried out in Jesus Christ, and it is a glorious success whether men believe it or not. “…what if some of them did not believe? shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect? God forbid…” (Rom. 3:3, 4). “…it is not as though the Word of God had failed” (Rom. 9:6, RSV). Christ declared through Isaiah, “And now, saith the Lord that formed Me from the womb to be His Servant, to bring Jacob again to Him, Though Israel be not gathered, yet shall I be glorious in the eyes of the Lord, and My God shall be My strength” (Isa. 49:5). Even the wrath of man praises God (Ps. 76:10), for in His unsearchable wisdom God causes even those who oppose the truth to work for the vindication of the truth (2 Cor. 13:8).

The Advantages of This Truth

If the freedom is outside of man, in Jesus Christ, and comes to man only in the gospel, it follows that a man is made free and kept free only by continually hearing the gospel.

* This truth makes the believer conscious that salvation must be mediated to him constantly. Unless he keeps hearing and believing the gospel, he will slip back into bondage (see Gal. 5:4; Rom.11:20, 21; Heb. 2:3; 6:4-6; 10:26-39; 12:25).

* This doctrine is truly preachable because it proclaims Jesus Christ as the elect Man (see Peter’s sermon in Acts 2:22-36) and exhorts even believers to make their calling and election sure by being diligent to be found in Him (2 Peter 1:5-11).

* Its view of man’s free will is Christologically based, and its view of election is Christologically based. Both man’s decision for Christ in time (Eph. 1:13) and God’s decision for Christ in eternity (Eph. 1:4-6) are possible solely because of Jesus Christ.

* It maintains the primacy of the legal aspects of redemption over the moral; justification over regeneration and sanctification.

* It can truly be proclaimed as good news to all men.

Those who believe that the Reformed church should also be a church that is always reforming will be open to these possibly new ideas while not rejecting old light passed on to us with no little toil and vigilance.

– This article is a condensation of three articles by the former editor that appeared in the July, August, and September 1976 issues of Present Truth and now appears inVol. 9 #2.

The Free Offer of the Gospel

Though it is plain that in the apostolic ministry of the New Testament the gospel was universally preached and freely offered to all, and that this was done constantly and sincerely, there are some who hold that to invite all to receive new life in Christ is an objectionable practice. They argue that the gospel invitation is for the elect alone, whose number and identity have been decreed beforehand, that the saving grace of the gospel is sufficient only for the elect, since, were it sufficient for more than the elect, there would be an excess of grace which would be wasted and ineffective, and that the offer of salvation is heard by the nonelect only for the purpose that they should reject it. It is an attitude that is governed by a strangely quantitative view of divine grace; whereas we are assured that “it is not by measure that God gives the Spirit” (Jn. 3:34). The grace of God is as boundless as his love. It cannot be weighed or computed. While the day of grace continues, so also does the report, “Still there is room,” and so also does the command, “Compel them to come in, that my house may be filled” (Lk. 14:22 f.). Was the invitation at first extended to those who for worldly reasons excused themselves from accepting it and thus excluded themselves from the banquet of divine grace a hollow invitation? Was St. Paul’s incessant preaching of the gospel and his becoming all things to all men that by all means he might save some misguided (1 Cor. 9:16, 22)? Was he wrong in his conviction that where sin is abundant grace is superabundant (Rom. 5:20)?

The intense urgency with which the apostles applied themselves to the task of evangelism is explained both by the commission they received from the Lord to preach the gospel throughout the world and by their awareness that the present period between the two comings of Christ is the period of the last days, which will be terminated by the last day, the day of final judgment for the unrepentant. The mainspring of the gospel is that God is the source of life, life indeed from the dead, and that no person is brought into being for the purpose of perishing. Accordingly, the prolongation of this final age is explained by St. Peter as the prolongation of the day of opportunity for sinners to repent and return to God though faith in Jesus Christ. He assures his fellow believers that, though the day of Christ’s return may seem to be long delayed, “the Lord is not slow about his promise as some count slowness, but is forebearing toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance” (2 Pet. 3:9). It was because “now is the day of salvation” that St. Paul willingly endured “afflictions, hardships, calamities, beatings, imprisonments, tumults, labors, watchings, hunger” as with single-minded dedication he proclaimed the Good News to all people (2 Cor. 6:1-10;11:23-29), and, further, that he urged that prayers should be made “for all men,” adding that to do this was “good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim. 2:1-4).

Why should Christians be exhorted to pray for all men, and how can it be said that God desires all men to be saved, if by a fixed decree many are destined never to be saved and cannot therefore be helped by our prayers? It only confuses the issue to argue (as e.g., Calvin does) that the Apostle does not mean all men as individuals but all orders or classes of men; nor is this contention confirmed by the specific mention of “kings and all who are in high positions,” as though this were intended as an illustration of one class of men, since the purpose of this particular specification is “that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life,” which is the condition that is desirable precisely because it is conducive to the free declaration of the gospel and thus to the salvation of all men. Thus St. Paul asserts later in this same epistle: “For to this end we toil and strive, because we have our hope set on the living God, who is the Savior of all men, especially of those who believe” (1 Tim. 4:10). This indicates that God reaches out redemptively to all men, but that only those who believe actually experience his redemption. If “all men” here means all classes of men, then “those who believe” must mean those classes of men who believe; but this is inadmissible since believing is the response of persons as individuals, not as classes. The obligation placed on Christians to be Christ’s witnesses to the uttermost parts of the earth follows from the fact that the propitiation achieved at the cross is cosmic in its amplitude (1 Jn. 2:2).

St. Paul leads us to the same conclusion in the comparison between Adam and Christ which he develops in Romans 5:12 ff…, where he asserts that “as one man’s trespass led to condemnation of all men, so one man’s act of righteousness leads to acquittal and life for all men” (v. 18). The argument rests on the exact numerical correspondence between the “one man” Adam and the “one man” Christ and between the “all men” affected by the sin of the former and the “all men” affected by the righteousness of the latter. In both places the action of one man has consequences that determine the destiny of all men. That “all men” means the entire human race, not just all the elect or all the nonelect or all classes of men, is evident from the declaration that “as sin came into the world through one man and death through sin, so death spread to all men because all men sinned”(v. 12), where “all men” indisputably signifies the whole of mankind. In Adam, therefore, there is perdition for the whole of mankind, and in Christ there is reconciliation for the whole of mankind. This being so, St. Paul is able, as we have seen, to speak of God as the Savior of all men and as wishing all men to be saved, to encourage the offering up of prayers for all men, and to require the proclamation of the gospel to all men.

In actuality, of course, all men cannot simultaneously be perishing in Adam and alive in Christ: the two conditions are mutually exclusive. As a matter of logic it would be possible for the whole of mankind whose status in Adam is one of perdition to be brought to the new status of redemption in Christ; but such universalism is unknown to Scripture, even though the potential may be said to be there. The reality is that the gospel which is offered to all for acceptance is rejected by many, and to reject Christ is to remain in Adam. The ultimate dividing line for the whole of mankind, then, is the line which separates those who are in Christ from those who are in Adam. Hence the offer of salvation is accompanied by the warning of judgment which gives it its true urgency, as is apparent from the frequency of admonitions such as the following: “He who believes in the Son has eternal life; but he who does not obey the Son shall not see life, but the wrath of God rests upon him” (Jn. 3:36). Those who thrust the word of grace from them judge themselves unworthy of eternal life (Acts 13:46) – a conclusion that is also taught in Romans 5:17; where St. Paul writes: “If, because of one man’s trespass, death reigned through that one man, much more will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man Jesus Christ.” Only the reception of God’s abundant grace and the acceptance of the free gift of righteousness can ensure the transition from death to life.

Within this perspective the gospel is freely offered to all persons throughout the world as the provision of divine grace for the rescuing of mankind from the predicament in which through their sin they have placed themselves; and it is offered in all seriousness as “the power of God for salvation for every one who believes” (Rom. 1:16). Through his gospellers God genuinely appeals to mankind to be reconciled to him (2 Cor. 5:20). To those rejecters of his grace on whom his judgment inescapably falls he still says: “I was ready to be sought by those who did not ask for me; I was ready to be found by those who did not seek me. I said, ‘Here am I, here am I,’ to a nation that did not call on my name. I spread out my hand all the day to a rebellious people, who walk in a way that is not good, following their own devices, a people who provoke me to my face continually” (Is. 65:1-3). Divine expostulation of this kind clearly indicates that there is on man’s part responsibility for accepting God’s grace as well as for rejecting it. Always the damning sin is the turning away from the grace and goodness of God which are there to be freely received. “What wrong did your fathers find in me that they went far from me?”, the Lord asked through his prophet Jeremiah; and then he accused the people of committing two evils: “They have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters, and hewed out cisterns for themselves, broken cisterns, that can hold no water.” It was not that God had abandoned them, but that they had abandoned God: “Have you not brought this upon yourselves by forsaking the Lord your God, when he led you in the way?… Know and see that it is evil and bitter for you to forsake the Lord your God” (Jer. 2:5, 11, 13, 17, 19). Thus they were chided, but without pleasure on God’s part. Even so God pleaded with his people to turn back to him: “Return, faithless Israel, says the Lord, I will not look on you in anger, for I am merciful, says the Lord. I will not be angry forever. Only acknowledge your guilt, that you rebelled against the Lord your God…. Return, O faithless sons. I will heal your faithlessness.” It is the cry of a father’s heart as he hopes and waits for the response: “Behold, we come to thee; for thou art the Lord our God” (Jer. 3:12, 13, 22). The appeal then made by God to Israel is now extended to all. God is at hand to do us good, chiding us with the reminder: “Your sins have kept good from you” (Jer. 5:25). Throughout Scripture God compassionately promises blessing to those who love and serve him according to his will, warns that those who rebelliously persist in ungodliness will bring judgment upon themselves, and entreats those who have wandered out of the way to repent and return to him. It is his grace manifested in and through the incarnate Son that creates the possibility for sinful men to make a positive response to his appeal.

The manner of God’s dealing with his human creatures is well illustrated by Jonah and his mission to the city of Nineveh. Jonah had been commanded by the word of the Lord: “Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry against it; for their wickedness has come up before me” (Jonah 1:1 f.). When at length, when being frustrated in his attempt to escape from this assignment, Jonah arrived in Nineveh, he announced the impending judgment of God: “Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!” The effect of this declaration was, contrary to what Jonah had expected, the proclamation of a fast and the putting on of sackcloth by the entire population, from the king down. “Let everyone turn from his evil way and from the violence which is in his hands,” the king said. “Who knows, God may yet repent and turn from his fierce anger, so that we perish not?” And the consequence of this change of heart, we read, was that “when God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil way, God repented of the evil which he had said he would do to them, and he did not do it” (Jonah 3:4-10). Jonah, however, was intensely displeased with the outcome of his mission, for he had desired to see the destruction, not the sparing of Nineveh – which shows how wrongheaded and lacking in compassion even a chosen servant of God can at times be. It was not as though Jonah did not know that God was a god of grace and mercy. “I pray thee, Lord,” he protested, is not this what I said when I was yet in my country? That is why I made haste to flee to Tarshish; for I knew that thou art a gracious God and merciful, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and repentest of evil” (Jonah 4:1 f.).

From this and many other places in Scripture we learn that God is not stearnly inflexible in his dealings with mankind, that even in his denunciation of judgment there is room for mercy, and that he is not, so to speak, self-imprisoned in a sequence of events that has been imprinted on all history prior to creation. The absolute sovereignty of Almighty God does no have to be maintained by him or safeguarded by us as it were casting it in concrete. His sovereignty is dynamic, not static, and it is not less real for being sensitive to the fluctuations among his creatures between rebellion and repentance. He is a personal God, and in all his dealings with personal creatures formed after his own image how should he not take pleasure in showing mercy where his warnings of judgment has caused men and women to cry to him for salvation?

That so excellent a servant of God as Calvin should have found it possible to assert that “God declared to the Ninevites… that he would do that which, in reality, he did not intend to do” is indeed surprising, for such an assertion posits (however unintentionally) a dichotomy between the word of God and the deed of God. It empties God’s warning of judgment, in this case, of all content. Nor is the problem eased by the postulation that the supposed incongruity between what God said and what God did is attributable to the controlling factor of his hidden or unrevealed intention, which is a type of rationalization quite foreign to the whole account. If the repentance of the Ninevites was fixed beforehand as the predestined consequence of the announcement of imminent punishment, which, however, God secretly had no intention of executing, how can it be said that “God repented him of the evil which he had said he would do to them”? (Such language, of course, means simply that God was moved by their change of heart to show them mercy instead of punishment. It is a human way of speaking about God: there was no wrongdoing for God to repent of; his “repenting” is descriptive of his sensitivity to the human situation; and certainly his judgment, when executed, is only holy and righteous, though, as it is experienced by man, evil in that it is the opposite of blessing.) Moreover, the qualification “yet forty days” indicated a period of opportunity for repentance, a time of grace, as the judgment was delayed. Thus the warning of judgment was not incompatible with the manifestation of mercy.

– This article was written by Philip Edgcumbe Hughes in his final book, The True Image – the origin and destiny of man in Christ and appears in Present Truth Vol. 9 #2. Dr. Hughes was an Anglican clergyman and visiting professor at Westminster Theological Seminary (Philadelphia) and published this book in 1989 just prior to his death. It contains the results of a lifetime of Bible study. This article is an excerpt (pp. 172-177) from the chapter titled “The Freedom of God” and is reprinted with permission from Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. We highly recommend this controversial book.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/5″ css=”.vc_custom_1578072058892{background-color: #dd9933 !important;}”][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar_page”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css_animation=”” row_type=”row” use_row_as_full_screen_section=”no” type=”full_width” angled_section=”no” text_align=”left” background_image_as_pattern=”without_pattern”][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”62px”][/vc_column][/vc_row]